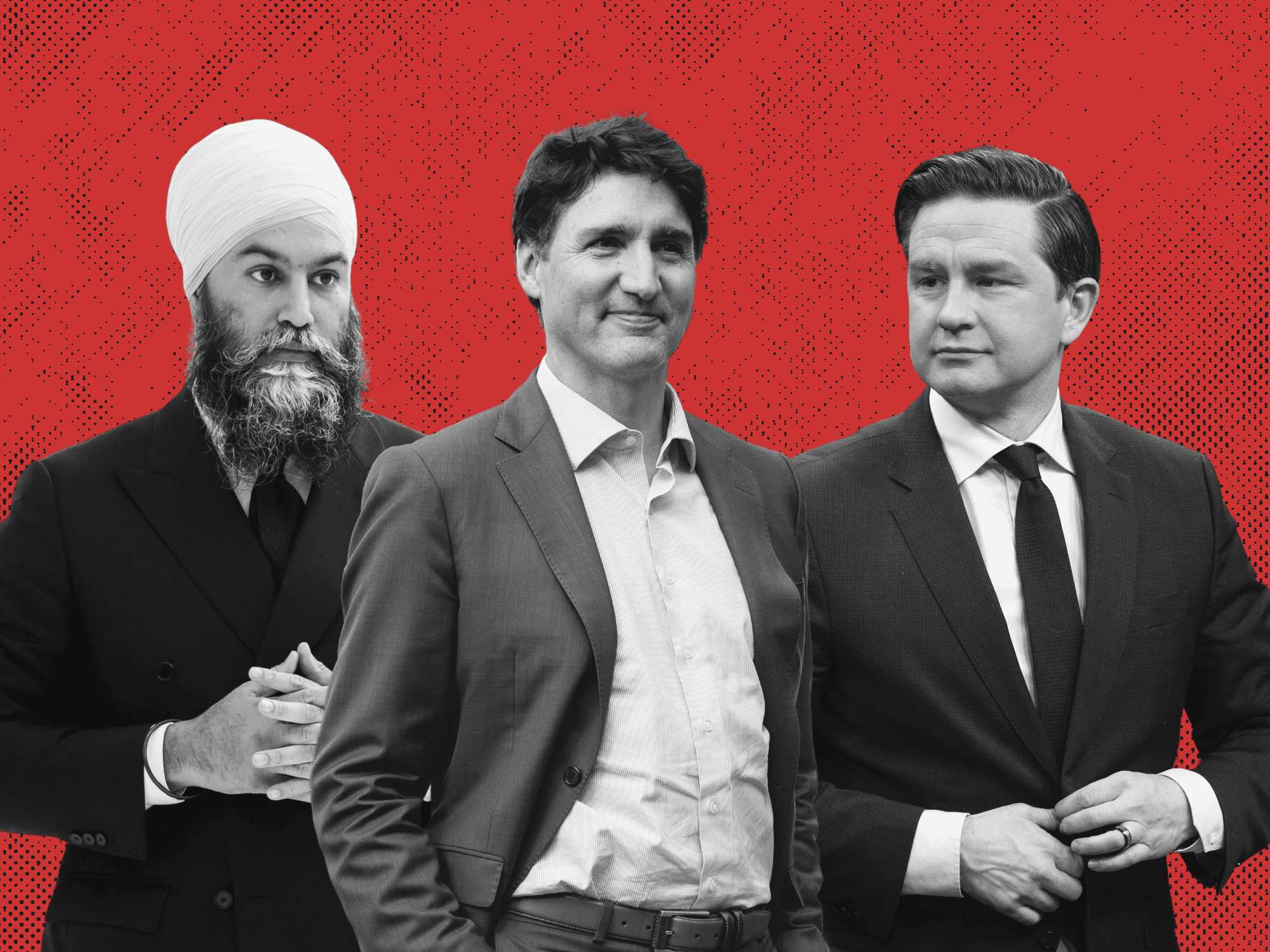

Meet the lobbyists connected to Canada's federal party leaders

An exclusive IJF network analysis helps reveal just who knows whom in Ottawa

28 Jun 2024 • 5 min read

Copied to clipboard!

Carly Penrose

Carly is a Toronto-based journalist. She holds a master of journalism from Toronto Metropolitan University. Her work has appeared in the National Post, This Magazine and The Canadian Press.

Democracy needs you.

Subscribe today to support independent Canadian journalism.

Dig Deeper

Our databases turn public records into public power. Dig in to find the real story on lobbying, donations, contracts, access to information releases and more.

Search